By Bill Zlatos

In 2000, Johnny Diaz fled the Dominican Republic and the rampant corruption and bribes that hampered his business career. He moved to Norwalk, Connecticut, where he got a job as a manager of a Walmart.

In the same town the following year, Grecia Vasquez was studying English as a second language when the late Hugo Chavez, then president of Venezuela, banned American currency, preventing her from using her credit card to fly home.

One fateful day, she walked into a local Walmart to buy a coffee maker and met Diaz. They dated, eventually got married, and had a child, Athena. The family moved to the Dominican Republic in 2012 but in time, they sensed again the winds of violence and instability. Of great concern then were the kidnappings of children and the ransom demands threatening murder.

They left the DR and moved to the Brookline neighborhood of Pittsburgh in 2018. Two years later during the pandemic, they launched SNACKEVER, an online business of healthy packaged treats. The company distributes 300-some products, which are grouped by category such as Keto, gluten-free, sugar-conscious, etc. for easy shopping. They also offer subscription boxes.

“We try to make the American dream,” Grecia Diaz says.

Entrepreneurs like the Diaz family are not unusual in the Pittsburgh region and U.S., according to recent studies.

“About one in five entrepreneurs in the U.S. is an immigrant, employing millions of native-born Americans,” reported the New York Times in August 2024. “They keep us fed and fill critical labor gaps as millions of baby boomers retire. These workers are the force behind much of our gig economy, driving our ride shares and delivering our food.”

Yet immigrants comprise only 5.8% of our region’s population, notes Christopher Briem, a regional economist at the University of Pittsburgh. This region, which suffers more of a population loss than most, ranks last for the rate of immigration among the 40 biggest metro areas in the country, he says.

“Were it not for immigrants coming into the region over the past 10 years, we would have lost population,” says Matt Barron, sustainability program director for The Heinz Endowments.

Between 2014 and 2019, the city’s population declined by 1.3 percent, according to the American Immigration Council. But without the 18.9 percent increase in immigrants, the city’s population would have dropped by 2.7 percent.

If the city’s population falls below 300,000, Barron warns, it could threaten its ability

to apply for certain federal grants. The Heinz Endowments has spent $9 million in the last six years to support programs helping immigrants and refugees.

Briem attributes the population decline to the city’s lack of jobs and entrepreneurship.

“We rank 40 out of 40 in entrepreneurial activity,” Briem says. It’s part and parcel (why) we lost so many jobs.”

Generally, he explains, two-thirds of a region’s economy provides goods and services. A city with a declining population offers little incentive to open a business such as a hair salon or a restaurant.

Immigrants are prime candidates for starting a business due to several factors, says Brent G. Rondon, senior international trade consultant for the Small Business Development Center at Pitt. They have to learn a new language and culture, for one, and many have survived violence and instability in their native countries. Some have endured a perilous journey to get here.

As a result, they are more inclined to take risks. Rondon further notes that immigrants, who typically lack credit when they arrive, will work multiple jobs, including weekends and most holidays, and save money to start their own business. Some even pay cash for a building to house it.

“They all see the whole country as an opportunity,” he says.

Take Grecia Diaz who sought help with her idea for a snack business from the Pittsburgh Hispanic Development Corporation, a nonprofit group that helps entrepreneurs overcome language barriers, and acquire permits and obtain loans, among other services.

Guillermo Velazquez, executive director of the incubator, says it has nurtured 160 businesses, 90 percent of which are still operating. Clients have created 130 full-time and 91 part-time jobs, he says, and most of the firms generate $50,000 to $100,000 in revenue during their first year and $1 million by their fifth year.

“First of all,” Velazquez says, “they contribute to the economic stability of the region. They pay taxes and create jobs. And they also satisfy a need in the region.”

SNACKEVER arose during the lockdown of Covid-19. Grecia Diaz noticed a need for healthy snacks for vegans, diabetics, gluten-free consumers and others with dietary needs. “We’re talking about good snacks with clean ingredients – snacks that are healthy, delicious and nutritious. That’s what sets us apart,” her husband says.

The family sells a variety of snacks – chocolates and trail mix, jams and teas – ranging from a bar of sea salt chocolate quinoa crisps for 65 cents to a bag of coconut rolls for $12. The Diazes even launched their own brand, consciouSnack.

“The food industry has many players,” Johnny Diaz says, so “getting name recognition is difficult.” The family targets customers needing treats for group gatherings such as schools and offices. The company sells about $200,000 in snacks a year and the plan is to reach $1 million in annual sales in two years, says Grecia Diaz.

Like many immigrants, the entire family pitches in. Athena does the marketing, including the snackever.com website. Her contribution to the business, along with her academic success as a senior at Seton-LaSalle High School, justifies their move from their families and native countries, says Grecia. The talented Athena, who sings and plays the piano, wants to be a performer and songwriter.

“I know 100 percent she will do it because we’re here,” her mother says with pride.

The American Way

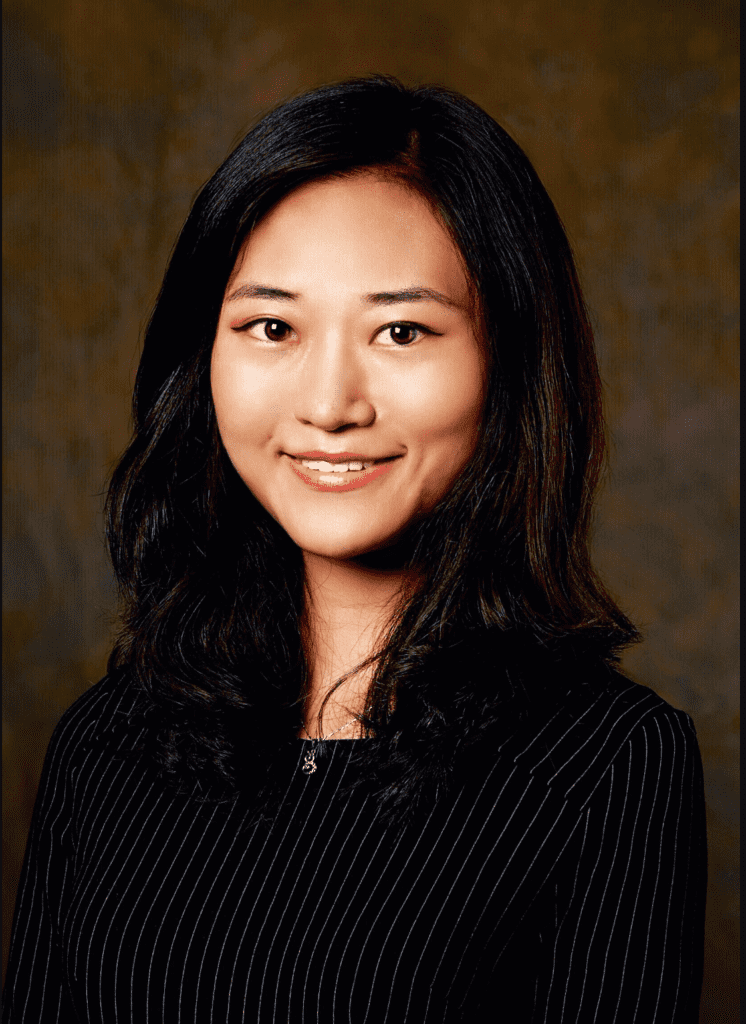

Growing up in China, JJ Xu was inspired by Hollywood movies such as Mission Impossible that she watched in a theater run by her grandfather.

“The gist of the movies and what the directors presented is the still the same,” she says. “The good people always win eventually. Work hard and hold onto your dream.”

Xu, now a Crafton resident, leveraged this nothing-is-impossible attitude to found TalkMeUp, an AI-based communication firm in Oakland. Her interest in communication can be traced to an unorthodox childhood in which her mother, an English teacher, encouraged her to compete in public speaking.

“The biggest thing I learned from my folks was not to be a ‘good’ child,” she says. “My mom taught me to speak up, which is the opposite of what most Chinese parents would do.”

After graduating from Peking University, Xu tried to start a business in China but could not get it off the ground for lack of mentors and capital. “Over here in the States,” she says, “…the sky’s the limit.”

In 2016, Xu enrolled in the MBA program in entrepreneurship at Carnegie Mellon University. The idea for TalkMeUp arose after Xu asked her classmates to rank the most valuable resource in an MBA program. Communication coaching topped the list. That was her lightbulb moment, seeing a huge opportunity in the training market.

Her first hurdle was getting a green card since investors hesitated to give money to an immigrant on a student visa. With her visa extended, she launched TalkMeUp in Oakland in 2018, and it went fully commercial last fall.

Her company evaluates online presentations and suggests improvements. The rubric judges speakers in such areas as facial expressions, eye contact, gestures, enthusiasm, persuasiveness and empathy. The advantage, Xu says, is that it removes the biases of human coaches.

So far, TalkMeUp has a patent for its software and 20 client firms representing 4,000 employees. Of those businesses, 90 percent renewed their contracts.

Xu, who acts as CEO of the firm, credits Pittsburgh for some of her success. “Every time I fly in at the Pittsburgh airport, the moment I touch down, you can feel how warm and welcoming Pittsburgh is with everyone from the interactions and small talk I have with local people,” she says. “In a city that’s innovative and forward-looking, we require that kind of culture.”

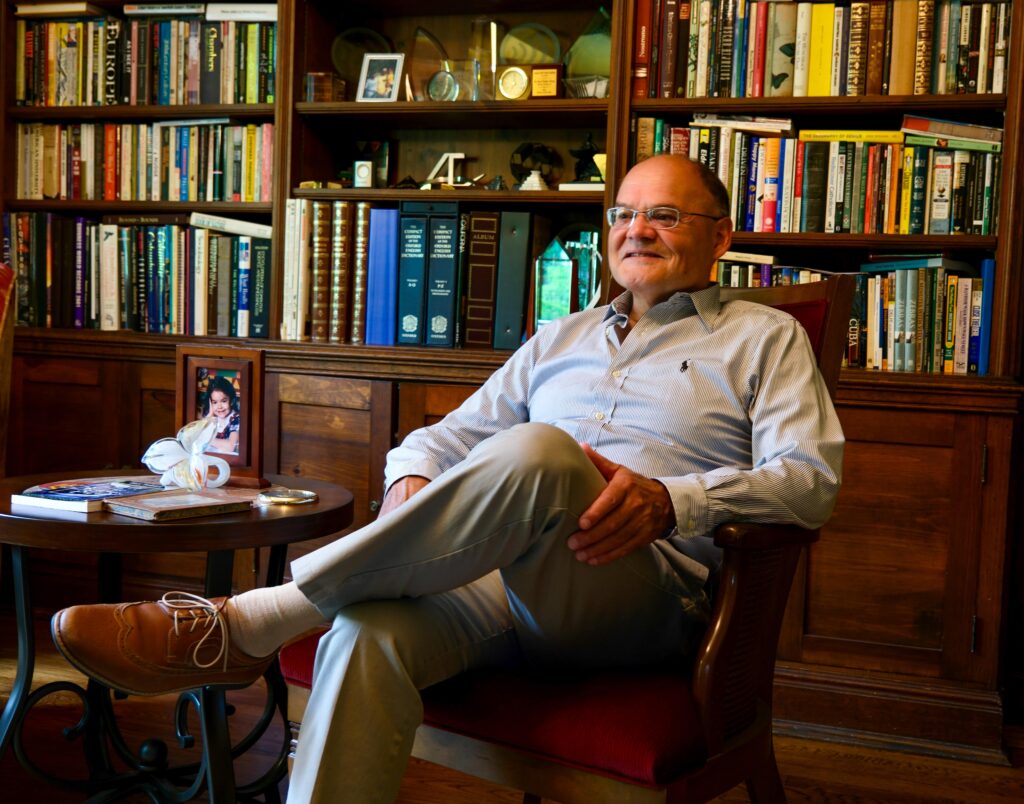

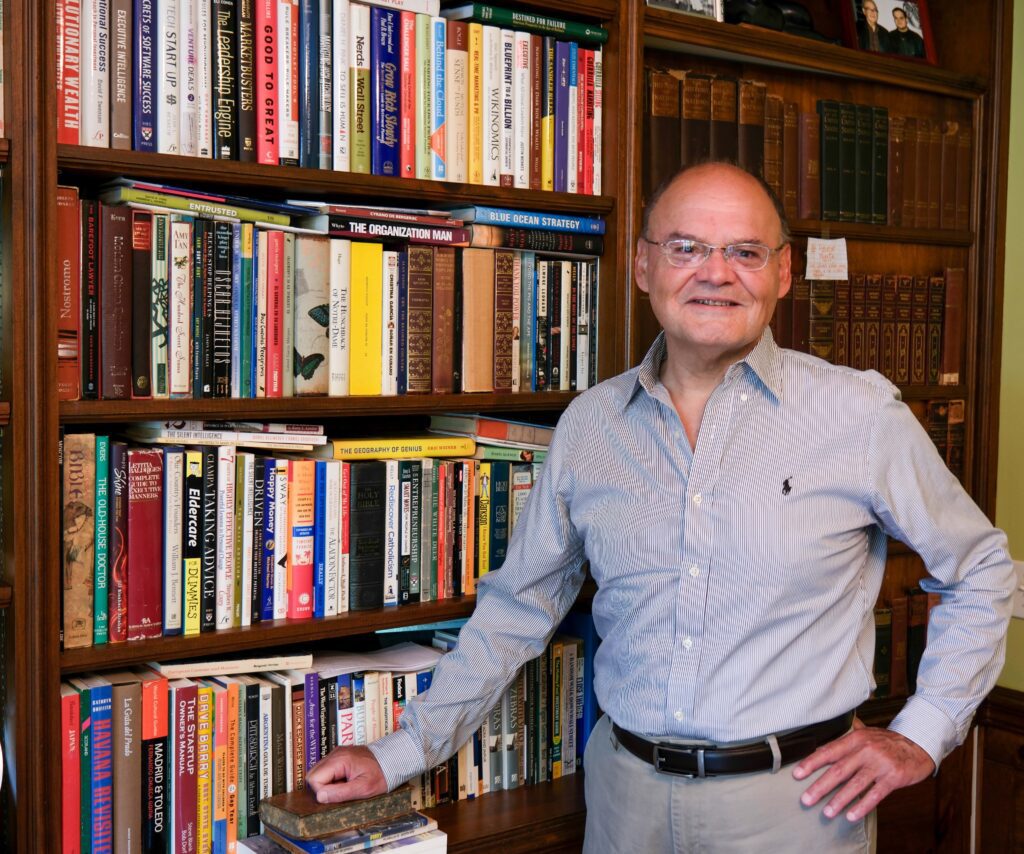

The son of immigrants

Like most Cubans, the family of Raul Valdes-Perez rejoiced at the takeover

of Fidel Castro in 1959. Then in 1961 Castro proclaimed himself a communist.

That meant Valdez-Perez’s mother, a teacher, would be forced to instill government propaganda in her students, and his father, an electrical engineer, would lose his small business. The family fled in September 1961, a month before it became illegal to leave. They dressed Raul, then 4, in beach clothes and told him they were going to the sea so he would not spill their secret.

The mother and three children instead went to the airport and flew to Miami. The father

later followed on the pretext that he was bringing them back. They all arrived in the United States with just the clothes on their backs.

After growing up in Chicago as the son of immigrants, Valdes-Perez graduated from the University of Pittsburgh, got a Ph.D. in computer science at Carnegie Mellon University, and launched a successful academic career there.

Hungry for a new challenge, he wooed an ambitious graduate student from France

to work with him on the campus. “Most people greet you with good morning,” Valdes-Perez says. “He would say, ‘When are we going to start a company?’

Eager to do so, Valdes-Perez asked CMU to change its restrictive rule preventing faculty from taking a partial leave of absence when they start a business. After the policy changed in 2000, says the Squirrel Hill resident, “My main concern was supporting a wife and three kids.”

He co-founded Vivisimo, which specialized in the development of computer search engines, with two other partners in 2000. Their idea of easing information overload by categorizing search results led to great success and the company was sold to IBM in 2012 for $147.5 million.

Not content to rest on his laurels, in 2015 Valdes-Perez launched OnlyBoth, a technology company that uses AI to analyze and benchmark company data to improve performance.

The accomplished serial entrepreneur finds the climate in the U.S. more conducive to starting a business than in other nations. “In this country entrepreneurial risk taking is encouraged, and failure will not be a lifetime stigma,” he says.

Less risk in striking out on your own

Prashant Ambe of Bridgeville moved from his native India to the United States in 1985 to get a master’s degree in mechanical engineering from Villanova University. He worked as a software executive for various companies, including Ansys, but he found the corporate world confining. “It’s almost like being in prison,” he muses. “You have to ask permission for everything.”

In 2004, Ambe founded BizOnWeb Inc., a firm that helps businesses build their internet presence, and in 2009, he launched Pittsburgh Homelist, a company that helps homeowners sell their property without a real estate agent.

He sold both companies in 2014 and 2015, and now mentors and invests in local startups. An angel investor, Ambe earmarks about $250,000 spread among 35 startup companies. Five have gone under, he says, but half are thriving. If they succeed, he could double or triple his investment.

Working in corporate America, with its culture of layoffs on short notice, is riskier than starting one’s own business, contends Ambe who was laid off from his first job in the U.S. after just three months.

“When you go through an experience like that, it’s scary,” he says. “If you have

a support system, which is not scarce in this country, the conditions are just right to get started.”

The New Americans is a first-of-its-kind journalism initiative with the mission to spotlight the contributions of immigrants to the Pittsburgh region, and ultimately to create a more welcoming and global city. The stories are available for free to all Pittsburgh media. Read more stories here.